By Anne Brodie

The chemistry is dense between Tilda Swinton and Idris Elba, co-stars of George Miller’s romantic fantasy Three Thousand Years of Longing. Swinton is Alithea, a narrologist, a scholar of stories who has chosen a life of intellect over love and is suddenly confronted by a Djinn – a genie from a bottle- while in Istanbul. He asks her to make three wishes and free him from thousands of years of loneliness, but she knows from stories that making wishes doesn’t end well. Their relationship soon becomes intimate and romantic, but philosophical rather than sexual. The balancing act between the actors takes your breath away, in Miller’s intriguing emotional adventure. We spoke with all three and they were frankly distracted by each other, so deep was the artistic and personal bond from making the film. Miller opens with the reason he cast them.

George Miller – The moment I met both of you I was struck. Once I met them I couldn’t think of anyone else.

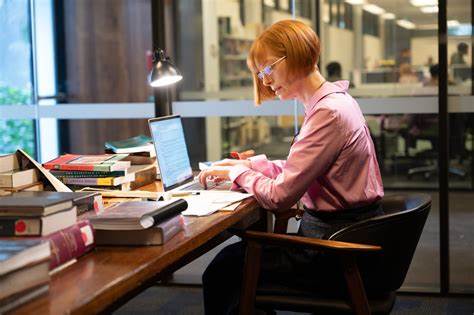

Tilda Swinton – Alithea is ready to jump in. She has curiosity, that’s the right word, curiosity. She’s self-aware, she declares early on as someone who finds feeling through stories, and sets out her stall for herself in a finite way. “I’m not going to feel much on my own account, I will feel through stories”. She admits to the Djin that she has a predilection to believe non-rational stuff. She might be rational, but she had a boy, an imaginary friend, someone who supported her psyche when she was a young person. This Djinn has to tell her his story so she just sits down and listens. Curiosity is an emblematic part of her nature.

Idris Elba – George’s version of the Djinn was page one, very much digested and internalised for what we set out to do – to be unique. It was on the page before I got there. We sat around for years and laid down the foundation and originality of this character and our collective ideas of who he was. It was important for me to steer away from our collective ideas of who he was. Important for me to steer away from ideas of what a genie is. His journey is only believable to audiences if we’ve never seen anything like this before. You are engaged in this character. And is he real? It was really important that we nurtured that version of him as an actor, a complete gift to create something.

George – We shot the flashback shots first, it was Idris’ recommendation and a brilliant idea. It was the second thing you said to me. Yes, I’d like to do that and then would you mind if we shot the stories first so when I find the hotel room I have experienced I can be this character? I’m working with a real filmmaker’s actor here. Two hours later I see a photo of you and Tilda sitting on the lawn at Tilda’s farm in Scotland, you turned Djin, bringing together and maturation.

Tilda – We had already been having these conversations for years. We had a fruitful and enjoyable week in London the year before where we threw it around together and then we were Skyping not Zooming yet and kept the conversation in the same room. When Idris and I arrived after Christmas, we were quarantined in the same hotel, where we Zoomed every day. One day we spent nine hours chewing cud. We talked through every syllable of the script. By the time we got to set we had water of the whole iceberg, we were confident and felt settled. Having said that, we still felt free thanks to George Miller. Even though we’d made decisions, we batted it back and forth through the takes. It was really wonderful, a long, long projectory of chewing it.

Idris – You could share vulnerabilities doing this; it takes your breath away, like being in space. Tilda’s reciprocal feeling was welcoming and I was open and nervous and her offering is as pure as it gets. All that vulnerability offers up the ability to feel safe. Actors freshen up so lines sound like the first time you’re saying them. Only when improvising or you know the text so well you can say it with people.

Tilda – Both Idris and I shared with George that we were both in the same state of your work, we both wanted to turn this piece of work into fresh snow and George was up for that. The way you do that is going around all the corners, putting the torch under every bit of wainscotting and looking at all the old stuff and you make up a new language on top of all of it.

George – The story asserts itself as a fairy tale. What’s really the advantage of telling these kinds of fairy tales is working with metaphor and symbolism that can be read by each person who experiences the film according to their world view and make order of it. They share the collective interpretations of each member of the audience and they are invited to experience it. The long tradition of storytelling about animals allows characters to be abstract and take away meaning. The circus was a big attraction, even with a poetic dimension in some way. Stories that are normal reporting of events are the ones that are most powerful and become part of the zeitgeist and mythology, allegorical.

Tilda – I was inclined to love George Miller. When I first met him I was embarrassed that I didn’t know it was George Miller that I cut off at a very fancy lunch. It was only after fifteen minutes I realised it was George, a great idol of mine, one of the most loving, interesting, curious people you would ever meet. He’s my friend, he’s extraordinary and a filmmaker. He’s a master. I was not fortunate enough to have worked with Hitchcock but I’ve worked with George Miller. Move over, Hitchcock. He understands cinema and how the camera tells a story like no one else. It’s been the privilege and joy of my life.

George – Directors who work with you (Tilda) have a kind of addiction to working with you.

Idris – What made the film irresistible for me besides working with George is that it is controversial in the sense that the Djinn is one thing but here it is another altogether. I’m going to play the Devil and evil spirits so for me, taking on this Djinn I was going for that. As an actor, it’s a challenge to do that in life and give it an entertaining spin. I knew nothing of Djinns so that was attractive. And I got to create an accent that didn’t exist, based phonetically, and I loved how it sounded.

Tilda – I can’t seem to escape acknowledging working on several stories playing immortals. She is a departure for me. I felt I knew now that I’ve seen her, I know her. She had to be built and we all worked together. She’s the avatar for the humans in the audience. It was a new and interesting road for me, to the point of attachment. She has shut herself down, made her decision to live alone and not have desire and to be intellectual and rational. At this point in her life, she feels herself change. It was a scary stereotype and we knew that and it was a family workout for all of us.

Three Thousand Years of Longing is in theatres Aug. 26