The very real dangers of AI victimisation as seen in Reuben Hamlyn and Sophie Compton’s documentary Another Body are brutal. Young women have been exploited by advanced AI, used by someone who intends to shame them, fixing their faces on bodies in pornographic videos in a seamless way. And the resulting footage can be disseminated at will, without the victim knowing. In this case, the main interviewee was surprised to see herself online in porn films, to her horror. She sought help so let’s see how that went. Last week What She Said’ Anne Brodie spoke with Reuben Hamlyn and now, a refresher with Sophie Compton.

Anne Brodie – What we learn in Another Body is beyond shocking. Were you prepared for what you saw and learned?

Sophie Compton – I absolutely did not know what we were getting into. The first few weeks delving into the 4chan threads were profoundly disturbing. What we saw on those forums was a stark expression of all the subtle currents of misogyny and objectification that aren’t normally spelt out so explicitly. It stayed with me, in my body. But it also fired us up to act. We felt like if we just looked away, and shied away from this brutal reality that we had uncovered, the perpetrators would win.

AB – Ruinous consequences for victims – the footage is out there. So they are vulnerable, professionally, socially and worst of all, insofar as compromising her mental health. what recourse does a victim have?

As there are no laws pertaining to deepfake porn federally or in her state the chances of a successful lawsuit are dim. The lawyers would have to come up with a suite of other possible charges and attempt to construct a case with that. There is no precedent. And because there are no laws, the police aren’t instructed to help her, and there are no frameworks through which she can emotional support. Her university followed the pattern of minimizing the issue that we have seen at every turn.

AB – Is that the case in Canada as well as the US?

SC – There are no laws banning non-consensual deepfake porn in Canada. Victims can try to build a case around privacy infringement, however, this lacks significant precedent. Although other forms of image-based sexual violence are addressed in Canadian law, deepfake porn itself isn’t included because it does not match what the Code defines an intimate image to be.

AB – Are there any protections in place, can we protect ourselves?

SC – In short, no. The only guaranteed way to protect yourself would be to not have any imagery of yourself on the internet because people can make deepfakes with just a single image. However, if we proposed that course of action, it would massively increase the ‘silencing effect’ whereby women and minoritized people are shut out from full participation in civic life. We believe it is important that we focus our efforts on stopping the behaviour of the creators and not the behaviour of the victims. Victims should be able to live their lives authentically, without hiding, shrinking themselves, or taking undue caution. To focus on what possible victims might do to prevent this might encourage victim-blaming attitudes – because even if let’s say someone was sharing intimate imagery consensually, if that consent is violated the responsibility needs to be laid at the door of the person violating that consent.

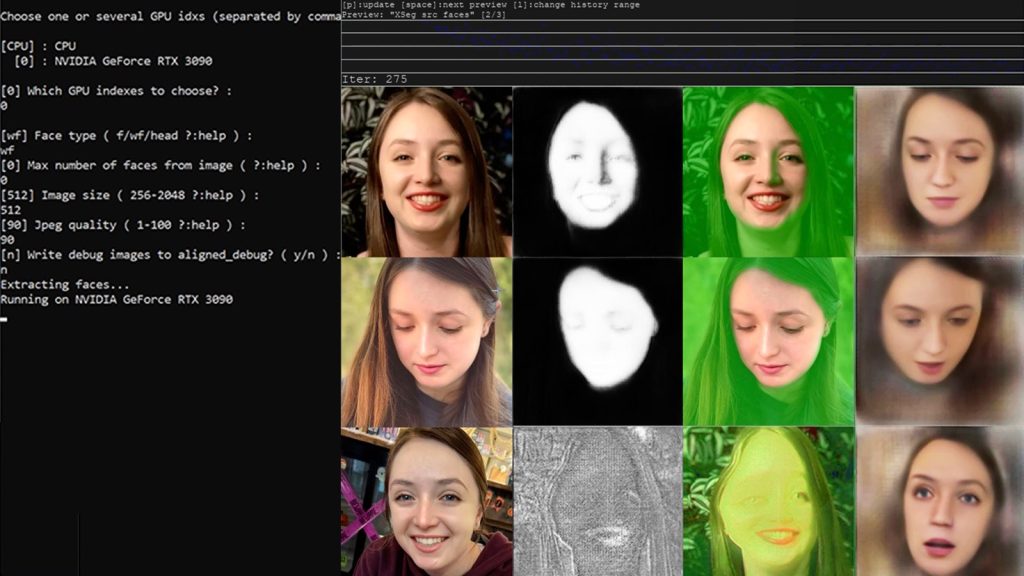

AB – You use deep fake tech to protect the victims’ faces and show how seamless it is. How hard are deepfakes to spot?

SC – At this stage, high-quality deepfakes are undetectable to the human eye. And it’s getting easier and easier to create deepfakes at that level. Things to look out for include blinking, the edges of the face, and slippage around the mouth. However, we should not expect that we will be able to identify deepfakes – our focus needs to be on the structures for labelling them where relevant and shutting down the misuse of this potentially powerful technology.